The East Coast of the United States of America boasts of a delicacy, so exquisite and indulgent, it can satiate even the most discriminating tastes. A true epicurean delight, the stuff of gastronomic dreams…

the Insomnia cookie.

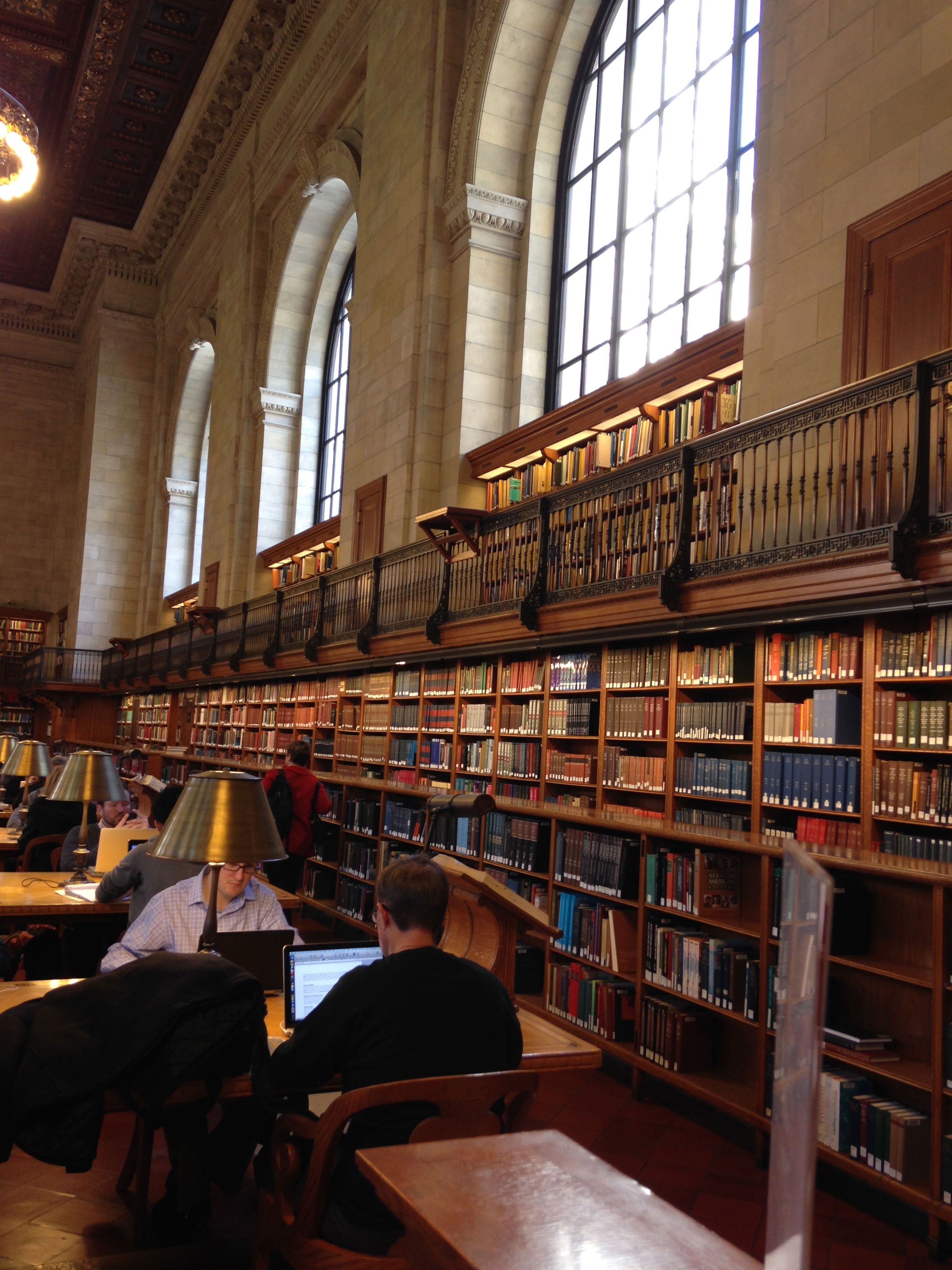

You wouldn’t think there would be any more to love in NYC– melting pot of a thousand cultures and passions, quick-witted liberals, good-looking strangers, and books oh god BOOKS!– until you stumble upon the neon sign the says “Insomnia Cookies” of this quaint little walk-up at 2:37 a.m.

The whiff of melting butter and fresh creme permeates every corner of this tiny, tiny shop/kitchen, squeezed between a Vietnamese restaurant and a Laundromat.

Coyly and without much eye contact, you huddle in with fellow insomniacs, also tensely pondering…TRIPLE CHOCOLATE CHUNK or SNICKERDOODLE DELUXE…shucks shucks tough decision, and finally giving in to both.

Unwrap the goodies at home, still warm and fresh.

Chunky and chewy all at once, each bite into the Insomnia cookie is like taking another step through a seamless ritual that is a prelude to a long and restful slumber.

In others words, carbs and chocolates relax the muscles, induce sleep.

Well… the other day I opened an old word file to revisit an academic essay I wrote in my previous class.

I found out that if I focused on every single word, read every single word of the essay with precision and the right dose of feelings, that by the third paragraph, I’d be fuzzy and loose all over, already half-dreaming.

Reminds me of the Insomnia cookie, my Insomnia essay.

Hmmm.

Academic essays are so cultured, well-mannered and invariably correct, they will either bore you to tears or bore you to tears.

However, fight the overwhelming desire to nuzzle the pillow, and you will be able to peel off the many layers of tedious and literary ostentatiousness (and sometimes, pretension) and finally, appreciate the Work for what it’s truly worth.

So only meddle with academic essays within your sphere of interests.

Also…

Writing the academic essay is like running a marathon. There’s months of mental, physical and spiritual conditioning. A lot of heartaches and body pains. Moments of self-doubt and resignation. And on the Big Day, the adrenaline rush and your quivering pride will push you to break your limits and see you through. Hopefully.

Example, for this academic essay (see below) : two months of research, two dozens books, journals, related texts, one out-of-town excursion, three very polite scientists, one scientific experiment, one legendary technocrat, five farming families, one road trip — Grace (our yaya) puked two consecutive times in the car, one fabulously stressed-out researcher (me).

Finally, the writing part, which usually takes a few days. I imagine this to be a breeze for the super academicians. Yeah, like William Moomaw, for instance, I’m sure he just sits down in front of his computer, sips tea, shrugs and coolly types away.

With me, it’s always one big, nasty production. First, I stare into space and spiral into a perpetual state of inertia. If there’s a time for regrets, it’s this time. Research too weak, data not enough, everything sucks. I’m never doing this again. Ever! I lock myself in the house for days to thrive on Diet Cokes and cheese fixes, shoveling Cheetos into mouth, as I wade through and try to make sense of the thousands of pages strewn all over the floor and on every flat surface. On the second day, my laptop screen is still empty, for sure, having not typed a single word. I panic and shake involuntarily (may or may not be due to caffeine), as my inner Ewok emerges. A very jittery, anti-social Ewok. Three days later, tear-stained cheeks and hair loss. I’m so out of it that I wouldn’t even remember the moment I finish writing.

The thing with academic essays is that every darn sentence has to be defended academically. Like if I say, the sun is hot, is totally unacceptable without spelling out the exact temperature, in Celsius and Fahrenheit, author, location, date of scientific research that empirically proves this statement. Can I say, surely, the sun is hot, because I’m sweating? But then I would need to quantify the amount of this sweat, the correlation between two variables, author location, date…Note that there’s also the proper way of arranging the above-mentioned author, location, date. The APA (American Psychological Association) version, for example, only allows the last name of the author to be written down with the first and/or second, third names to appear only as initials in the Bibliography Section. Moomaw, W. Sachs, J.D., Beresford-Cooke, C.

Someday this will all make sense.

Winning the Green Revolution

By: Apples Jalandoni

Parts 3 and 4 of a 4-part Insomnia er academic essay

III. The Green Revolution’s Legacy : Climate Change and Rice Production in the Philippines

Eric embodies a typical rice farmer in the Philippines today: male, married with children, uneducated and has only rice farming as his family’s source of income. In an interview for this paper (April 23, 2013), Eric, who has been rice farming for fifteen years, expressed his disappointment at the most recent dry-season’s (January to April) low yield. His efforts only got him 130 cavans of rice grains per hectare, when he is used to producing 180 cavans or more in the past years. Eric attributed the low yield to the extreme heat during the dry-season that resulted in a lot of empty rice grains. What is even more worrisome, he said, is that the next season, the wet-season from June to October, is expected to produce only 50 cavans because of the effects of inclement weather during this time and the onslaught of typhoons.

Like Eric, most Filipino farmers today use one or more of the inbred rice modern varieties that were first developed and distributed during the Green Revolution. Recently, hybrid varieties from agricultural biotechnology companies also became available in the market.

However, in spite of these technological advances, agricultural production is still at the mercy of the ever changing climate.

A report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (2009) linked agriculture to climate change. Climate change threatens agricultural production through higher and more variable temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and increased occurrences of extreme events such as droughts and floods.

On the other hand, agriculture is part of the climate change problem, contributing about 13.5 percent of the annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (IFPRI, 2009), compared with 13.1 percent from transportation.

The Philippine Rice Research Institute (Phil Rice) is a government corporation under the Department of Agriculture that is mandated to conduct research on the Philippine rice economy.

A March 2013 study by Phil Rice’s lead researcher, Dr. Flordeliza Borday, and her team, found a correlation between climate change and the decrease in rice yields throughout the country. In an interview with Borday for this paper (April 22, 2013), she said climate change manifests in the Philippines through warmer days and extreme precipitation patterns. Sometimes the duration of rainfall would be too short while at other times, there would be massive downpours.

According to Borday, when the night time temperatures go up, instead of the plant using its energy for grain production and filling, it will use its energy for its maintenance respiration. This will result to many unfilled grains and thus, the low yield.

Borday also said that the amount of rainfall can affect rice yields. For instance, when there is too much rainfall, rice submergence becomes a major constraint to production. However, when there is very little water supply, the non-irrigated rice fields also suffer.

According to the Climate Change Commission, a government policy-making body on climate change, the Philippines is one of the most vulnerable countries to the impacts of climate change because the country is exposed to multiple hazards like tropical cyclones, floods, landslides and droughts that affect agricultural output.

There is more alarming news for the Philippines because the country’s weather bureau, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), projected that mean temperatures in all areas in the Philippines are expected to rise by 0.9 to 1.1 degrees Celsius (33.62 to 33.98 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2020 and by 1.8 to 2.2 degrees Celsius (35.24 to 35.96 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2050. Moreover, according to PAGASA, hot temperatures will become more frequent in the future.

The March 2013 Philippine Rice Research Institute (Phil Rice) study on climate change and rice production used weather data from selected agrometeorological stations that were most proximate to the major rice growing areas of each region in the Philippines. The weather variables included were daily minimum temperature and rainfall.

Borday and her team analyzed the weather patterns in the Philippines. They found out that the five-year average of minimum or night time temperature in the first and second semesters of the year have both increased by nearly 1 degree Celsius (33.8 degrees Fahrenheit).

The minimum temperature during the dry-season has a negative effect on the average rice yield. In particular, a 1 degree Celsius (33.8 degrees Fahrenheit) increase in minimum temperature during summer, decreases yield by 64 kg/hectare (Borday et al., 2013).

Similarly, rice yield diminishes by 36 kg/hectare for every 1% increase in the share of wet days. This is in relation to lower solar radiation during wet days which results to lower energy for photosynthetic activity (Centeno and Wassman as cited in Borday et al., 2013).

The average gross income per hectare also has a negative correlation to the increase in share of wet days. On average, a 1% increase in the share of wet days decreases farm income by Php 356 (8.71 USD) per hectare (Borday et al., 2013).

IV. Winning the Green Revolution: Learning From the Past to Forge a Sustainable Future in Rice Production

Fifty years after the dawn of the Green Revolution, the Philippines still struggles to produce enough rice to feed its people. The country has always needed to import rice to fill the gap between domestic production and consumption. With a 2% annual population growth rate and a steady increase in per capita rice consumption, imports will most likely continue to play a major role in meeting domestic demand (Borday, 2010).

Moreover, the Philippines has long ago maximized the 4 million hectare land area for rice production. As a nation of islands without any major river deltas, the country is also at a disadvantage when it comes to agriculture. Located off the eastern edge of the Asian continent, the Philippines bears the brunt of numerous typhoons, making rice production more difficult and risky (Dawe et al., 2006).

While rice production in the country experienced a slight upsurge during the decade of the Green Revolution, nearly all Filipino farmers have adopted this technology package. Thus, it can no longer contribute to further growth (Dawe et al., 2006).

Today, the struggle for rice sufficiency continues, amidst a ballooning population, scarcer resources and a rapidly changing climate.

It is imperative that lessons from the Green Revolution would be learned so that mistakes are not replicated.

For one, the development and distribution of inbred rice modern varieties resulted in a colossal loss of traditional rice diversity in the country and throughout developing Asia.

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) purposely developed modern varieties that were suited to irrigated and favorable rain-fed environments because of the low research cost of producing new technologies for these area. A large amount of basic research knowledge already existed for irrigated rice, and the probability of success for applied research in that environment was believed to be higher (David and Otsuka, 1994).

However, a developing country like the Philippines which cannot afford to maintain massive irrigation systems, would not also be able to provide a favorable environment for these modern varieties in the long run. That is why the Green Revolution technology not only reached a plateau in terms of productivity but also took a downward spiral when hit by harsher climatic conditions.

Traditional rice varieties, on the other hand, were overtaken by the Green Revolution technology. Thus, further studies on these varieties became stifled so that very little knowledge of their qualities have been documented. Researchers at the Philippine Rice Research Institute (Phil Rice) have only recently begun collecting traditional rice varieties for analysis and experimentation. In an interview for this paper (April 22, 2013), Phil Rice science research analyst, Celia Leano Diaz, said that some traditional rice varieties have traits such as pest resistance and drought tolerance that cannot be found in modern varieties available in the market today. According to Diaz, they are studying the possibility of re-introducing some traditional rice varieties in selected areas where these could thrive.

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) where the Green Revolution began has also been busy discovering new rice varieties that can adapt to climate change. For instance, the IRRI has developed flood tolerant varieties called scuba rice that can withstand submergence even for a couple of weeks (Barclay, 2009).

However, for a rice sufficiency program to work, there should be a comprehensive and unified effort to support its implementation, much like the success of the initial diffusion of the Green Revolution technology. This could driven by the private sector or government-led. For Jesus Tanchanco, the Philippines’ ex-Food Czar, what is needed is a strong political will from the nation’s leaders to prioritize food security.

On the day that the IR8 was released on November 28, 1966, the IRRI announced that any farmer who came to IRRI could pick up two kilograms of the new seed free of charge. Local government officials as well as technicians from the Bureau of Agricultural Extension did not only distribute seeds to the farmers, they also conducted on-farm demonstrations. The government also initiated an extension-credit-input package program intended to promote diffusion of the new rice technology. The package included supplying credit to farmers without collateral for them to purchase seeds, fertilizers and farm equipment (Hayami and Kikuchi, 2000).

Agricultural biodiversity constitutes a significant portion of the global biodiversity that has direct use value. Modern rice varieties that are dependent on fertilizers and chemicals have led to the degradation of rice field environments and even adversely affected human health. To combat these problems, rice-aquaculture and integrated pest management (IPM) could be alternatives to intensive rice monoculture. In the Philippines, rice-aquaculture involves low-cost fish production in rice farms. IPM seeks to minimize pesticide use in rice growing. This offers a way to integrate rice-aquaculture with IPM, the aquatic organisms being an additional incentive not to use pesticides (Horstkotte-Wesseler, 1999).

Finally, while rice production is adversely affected by climate change, it also contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), rice is often grown in flooded fields under anaerobic soil conditions that release methane as organic matter decomposes in the soil. Methane is a greenhouse gas that is about 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. IRRI is now promoting alternate wetting and drying as an alternative management practice that reduces the amount of time rice fields are flooded and can minimize the production of methane by 60% to 90%.

Moreover, crop residue burning which loads carbon dioxide into the atmosphere should be stopped. This is still being practiced by 90% of rice farmers in the country (Mendoza and Samson, 1999).

However, while the development of sustainable technologies is crucial in achieving rice sufficiency, the farmer should not be forgotten.

One of the major causes of the Green Revolution’s failure was the lack of education of the farmers so that they were not able to keep up with the new technology (IFPRI, 2002).

Farmers must now be trained to improve their decision-making skills and understanding of ecosystem processes. Issues such as labor constraints, insecure property rights and difficulties in organizing collective actions should be seriously addressed.

By building on the strengths of the Green Revolution and avoiding its failures, stakeholders in rice production– from policy makers to scientists to farmers– can take significant steps towards achieving sustainable food security for all.

P.S.

Hey, thanks for sticking around!

2014 is the Year of the Horse. A year that promises to be gentler and kinder, a respite from the very difficult (and catastrophic) Snake Year.

You know, this could be a lucky year for us! Well, that is, according to the Chinese. It’s true, the Chinese believe in luck. But take it from me, they believe in hard work more.

My mother used to say, why don’t you work hard like the Chinese!

My parents were so impressed by the Chinese that my sister and I were made to study in a Chinese Jesuit school from Kindergarten to High School. So we studied their language and culture for more than 12 years.

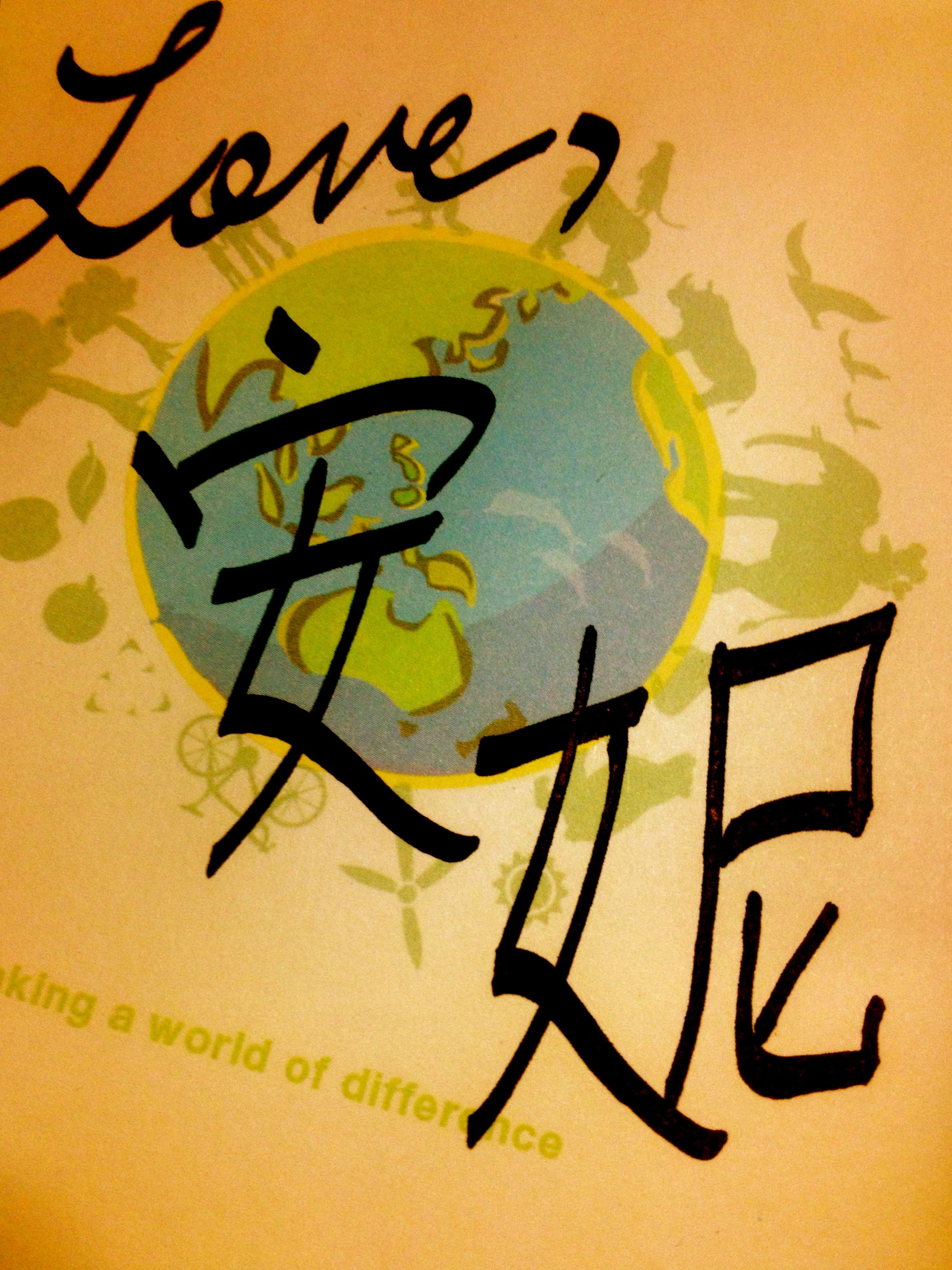

And since my parents are not Chinese, it was up to the School to christen me and my sister with our Chinese names.

I remember our Principal excitedly announced to me: Your name is going to be Ann Nee! Which means Peace Girl.

I must have looked confused, because the Principal continued, this is perfect for you because you’re going to be a woman of serenity, harmony and calmness.

Oh I see, I gushed, that’s so very nice, thank you!

Then they went on to name my sister Ann Mei.

Which means Beautiful Girl.

Life is truly unfair.

Kung Hei Fat Choi! Happy New Year!

Kung Hei Fat Choi! Happy New Year!

Love,

Chinese New Year the Filipino way!

Cheers!